IPEM Cannes 2024 – The Daily Spin – January, 25th

The shifting role of LPs was the overarching theme for the morning session of Day 2, at the 10th edition of IPEM in Cannes. After a full day of yoga,…

The next decade, and beyond, represents a key staging post for private markets. The fact is, more companies are choosing to stay private for longer, as the route to going public is increasingly viewed less favourably by company founders and entrepreneurs.

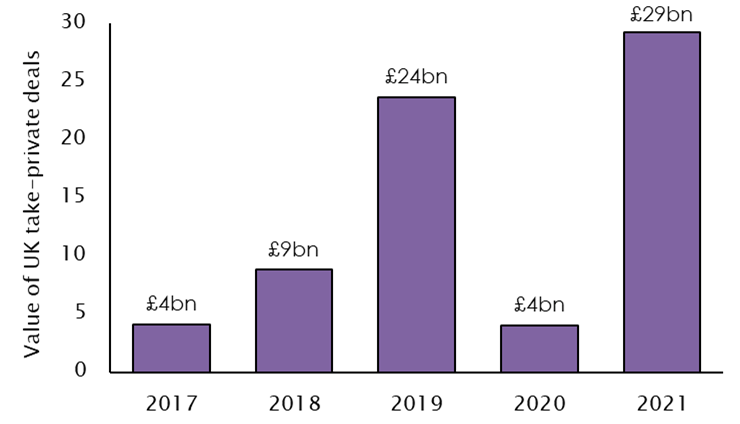

Moreover, private equity groups continue to target large established companies to take them private; for example the $16.5 billion acquisition of Citrix Systems by affiliates of Vista Equity Partners and Elliott Management. According to Reuters, PE firms spent $226.5 billion on such deals in the first half of 2022, up 39% on 1H21. In the UK alone, the total value of UK listed companies taken private increased from £4 billion to £29.3 billion last year.

As private equity wields further influence on capital markets, it is likely to change the way people view the industry. Remaining private means no quarterly disclosures and reporting obligations to investors, meaning less visibility, less accountability and less ability for the broader public to understand how companies are being run. When this applies to vital areas of the economy, such as Healthcare, Media/Advertising, Technology and Energy Transition, it could lead to increasing unease among the general populace – not only in Europe, but globally.

It therefore stands to reason that PE firms will attract greater attention from media, government and regulators as they put record amounts of dry powder to work in the coming years, targeting more public companies: especially for those GPs running ‘mega funds’ of $5 billion plus. Understanding exactly what the consequences will be, in a wider economic context, is hard to say at this stage. One thing that is clear, however, is that as private equity’s sphere of influence grows, it will need to embrace a willingness to engage publicly and demonstrate the positive effect it is having on the economy, on the climate, on jobs etc.

Innovation drives job creation

Within Europe’s economy, private equity has helped to accelerate job growth in areas such as Information Communications Technology (ICT), Biotech & Healthcare, and Energy & Environment. Leading European cities are embracing innovation with Berlin, Luxembourg (more broadly) championing Fintech. The Ile de France region around Paris has the largest concentration of private equity backed jobs with more than 1.4 million people working for PE-backed companies.

How GPs demonstrate this positive multiplier effect on job markets will take on greater import as Europe’s PE marketplace expands. Doing so could go a long way to assuaging public concerns.

Indeed, private equity still suffers from an image problem. Jonathan Angell, partner at law firm Dechert LLP, has said that the boom in acquisitions by non-UK PE firms “has also generated commentary to the effect that PE is draining UK businesses – the returns generated are flowing out the country, to international investors, and leaving the UK.”

Of course, by remaining private, it prevents traditional investors from sharing in wealth creation, which they enjoy when receiving dividends from listed companies. That avenue of return is getting choked off, and partly explains the comment above. How does private equity contribute to the wider benefit of society if all of the wealth is concentrated in the hands of a select group of investors?

Eric de Montgolfier, chief executive, Invest Europe, responded recently to a question on the topic of those who criticise private equity, stating: “Private equity-owned companies employ 10.2 million employees which represents 4.3% of the entire European workforce, which is huge for a single industry.” In his view, the industry is uniquely placed “to play a meaningful and positive role in achieving the climate neutral goals”.

Regulation will require GPs to be more transparent on ESG-related issues. In March 2021, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) came into force. This will require private market fund managers to increase disclosures about their investments and their operations. As pointed out by Skadden in a recent article, some private capital firms may have to alter their behavior rather than make adverse disclosures that could be detrimental to their public profiles. “For private capital firms, this means a new era of public scrutiny, where an increasingly wide base of stakeholders will seek to hold them to account,” they write.

The battle for talent

One key area of further improvement is the issue of talent and diversity in private equity, where it remains behind the curve. Investors, however, are becoming increasingly focused on the diversity of investment talent. Attracting the very best of the next generation will become a key battleground in 2023.

Speaking at the IPEM event in September, Helen Steers, Partner at Pantheon, confirmed that D&I has been incorporated in to Pantheon’s DD questionnaires: “The more diverse the better performance, and his is an industry that lives and dies by performance. By casting the net wide, we can avoid groupthink.” Neuberger Berman has committed to 60 funds and those who deliver the best performance “are diverse funds”. “We conduct a diversity survey not just to understand what their team looks like but also what their views are. Where do they want to go? We hold them accountable,” said Patricia Miller Zollar, Managing Director.

Being able to present an exciting work environment that challenges people intellectually, and makes them feel as though they are working for something bigger and more meaningful than the four walls of the corporate office, is a challenge that all GPs face but one they are more than capable of rising to.

According to EY, the number of females on investment teams is slowly rising and, over the past few years, there has been a slow decline in the proportion of all-male firms. Organisations such as London-based Level 20 continue to play a key role too, providing mentoring and inspiring the next generation of talent.

By investing in diversity and inclusion, private equity will find that it is able to more broadly reflect society and its growing influence in the global economy. Doing so could lead to greater positive appeal.

The Morning of Jan. 25th – Day 2

Morning POWERTALKS

Theme: After The Reality Check, The Road Ahead

2023: A Historic Stress Test For Private Market Portfolios?

After The Reality Check, The Road Ahead | KEYNOTE

Why General Public Acceptance Is Key For The Next Decade

Does The PE Industry Have A Talent Crisis?

Changing The Face Of Capitalism, A New Roadmap For Private Markets | CLOSING KEYNOTE

Morning SUMMITS

CLIMATE INVESTING SUMMIT

(Sponsored Summit)

Morning SOCIAL EVENTS

SINGLE FAMILY OFFICE LUNCH

(Sponsored Event)

IPEM CANNES 2023 SUNSET BASH

(Sponsored Event)

The shifting role of LPs was the overarching theme for the morning session of Day 2, at the 10th edition of IPEM in Cannes. After a full day of yoga,…

Fill-in the information below to submit your event.

Fill in the information below to download the Survey.

Fill in the information below to download the Product Catalog.

Fill in the information below to download the Investor Package.

Fill in the information below to register as a journalist.

Fill in the information below to download the Factsheet.

Fill in the information below to download the Product Catalog.

Fill in the information below to download the list of firms.